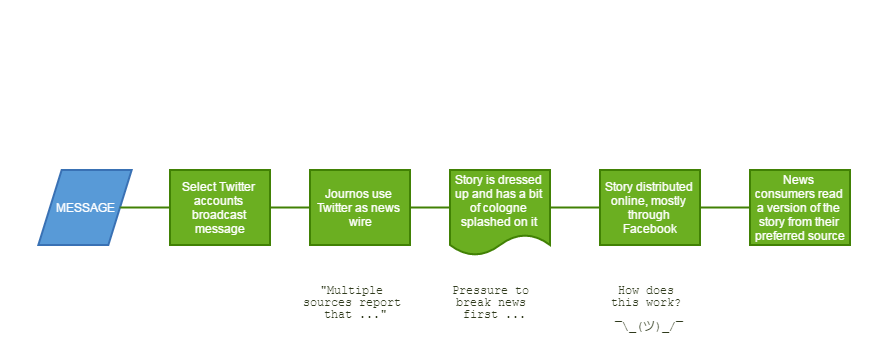

The world of politics and media in the US is mildly aflutter this weekend after a man most people hadn’t heard of before ran an extended advertisement for his services. Ben Rhodes is President Obama’s deputy national security director for strategic communications, also known to some as “the Boy Wonder of the White House” and the New York Times magazine has a long profile of him. After some interesting background colour about just how an aspiring novelist ended up writing the President’s speeches and directing large chunks of American foreign policy, the piece gives an extended description of how Rhodes and his team shape and disseminate their message across the 2016 media landscape. It’s interesting enough that I even got my crayons out and attempted a chart.

A lot of the ire has been directed at the disdain Rhodes and his boss show for journalists who “literally know nothing”, how dishonest their selling of the Iran trade deal to the public was and how deeply cynical the administration’s playing of the message management game is. ‘Ben Rhodes, Liar’ says the Free Beacon . ‘A stunning profile of Ben Rhodes, the asshole who is the president’s foreign policy guru’ thunders Thomas E. Ricks in Foreign Policy. ‘Why the Ben Rhodes profile in the New York Times Magazine is just gross’ grumbles Carlos Lozada in the Washington Post.

Of these three (and there are plenty more out there), the last one is closest to my thoughts on the profile. There are lots of repugnant aspects to the piece, but none of it strikes me as particularly new. Perhaps it’s never all been stated so arrogantly and bluntly in one place before, but most of the media insiders complaining can’t be unaware of the access journalism game. And I certainly can’t think of a better, more high profile example of access journalism and all the trade offs it requires than the White House beat.

Some of the resentment may come from the methodology of message dissemination described in the piece, which does an end run around some formal, hard won relationships and uses social media to seed and spread the word. The use of Twitter is focussed on in the piece, with only passing reference to Facebook, but to my mind that’s where the really concerning black box stuff is happening.

…

So far, so straightforward. The message is decided on, willing hands help push it out through Twitter, with Price’s additional colour added. Other busy and probably desk bound journalists, using Twitter as a supplement and enhancement to traditional wire services write up the story and give it some presentable clothing, as they have seen it appear from multiple sources on Twitter. Then they in turn press publish.

The story appears on news websites but the numbers who read them there are falling. It also shows up on the publication’s Facebook pages and the machines get to work.

As an end user of Facebook, you’ve very little control over what you see in your feed, and very little ability to shape what Facebook’s algorithm decides you will see, when and in what order. There’s an increasing chance that a typical Facebook user gets much or most of their written news through Facebook. As an aside, Facebook would now also aggressively like their users to get much or most of their video news through Facebook. This will happen. Facebook has the scale to do this.

Anyway, back to the print story wending its way though Facebook’s entirely opaque plumbing – a wondrously complicated plumbing system liable to change on a whim. This story shows up in users’ feeds with the message present and correct from a large number of potential news sources. Window dressing around the message has been duly applied, so the stories from different outlets won’t be exactly the same.

The majority of American adults are Facebook users, and the majority of those users regularly get some kind of news from Facebook, which according to Pew Research Center data, means that around 40 percent of US adults overall consider Facebook a source of news.

(from Emily Bell’s ‘Facebook is eating the world’)

In addition to inscrutably dropping news stories from news organisations into users’ feeds, Facebook also does a little bit of curating of its own. The takeaway of concern for journalists here is obviously that Facebook is mostly interested in journalists as a means to train up its algorithms.

None of the platforms, of which Facebook is indisputably the largest, can be neutral actors in this world. They create the algorithms which now decide which news is presented to which user. In this case, news that has one message from one source, although there is a comforting illusion of a diversity of sources.

Perhaps I’m reading too much into this. After all, Mr. Rhodes is just advertising his availability for work next January. Prospective employers, if you’re listening, Ben would quite enjoy some time in the sunshine in California.